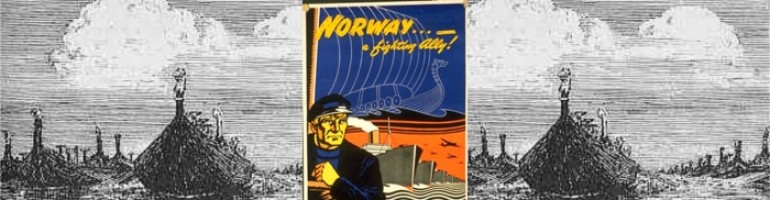

Actual fighting began in 1938. It didn’t go well for Norway, but it did make for exciting AAR-writing, with famous last stands, partisan risings in strategic bottlenecks, militias holding mountain defense lines against tanks, and dramatic swings of fortune.

June 1st, 1938

Burgundian/Norwegian border, Germany

The border country was old, and steeped in war. Men had landed here in long ships with dragon prows; had set out from stone castles to fight mailclad from horseback; had drilled in disciplined ranks of musket and pike. Now great metal towers whirled where the sentries had stood, keeping their eternally vigilant watch on the sky, and the fortifications were concrete and steel; but the business of war was the same, and the land knew it well.

It began, not with the howl of bomber aircraft that so many had expected, but with the familiar rending crash of a thousand guns firing in unison. Then came the tanks, hundreds of black, crawling insects, their infantry following behind in ordered ranks. The reply was instant: The long guns stuck heavy snouts out of their bunkers, belching tongues of flame bright even in the predawn light, and behind them the crews of heavier guns rushed to their stations.

There had been war in these lands for a thousand years. News of the attack flashed across the ether as fast as operators could warm their crystals; but the Ynglings had never been ones to give over a tradition, if it could be fitted in with newer ways of war. All over the Norwegian Realm, sirens called citizens to their war stations; and on the mountains an older form of warning came into action.

All along the craggy coast the beacons blazed.

————————————————

The Belgian attack came at the worst possible moment for the Norwegian-Polish alliance. Trusting that internal Burgundian politics would shield them for another year, the Yngling ruling caste had decided on a major overhaul of its army, necessitating a long cycle of retraining and equipment familiarisation. At the same time, it had been late in giving the puppet government of Poland permission to upgrade its military to the latest standards. If these two overhauls had been completed, a much more dangerous military machine would have faced the 150 divisions of Burgundy’s Army of the Elbe. However, the Ynglings had underestimated the pugnacity of a nation whose rulers were not compelled constantly to demonstrate their instant readiness to put down any challenge to their authority. The difference between the Revanchist and Conservative factions was not in whether Norway should be attacked, but in when, with the Revanchists favouring immediate all-out attack under any circumstances. Seeing a chance to attack on favourable terms, however, the Conservatives under van Zeeland were happy to make a bid for European hegemony, which the Ynglings found themselves ill prepared to resist.

The initial attack, thus, swept both Norwegians and Poles eastward past the Oder; though the narrow peninsula of Denmark was held for a while, massive armoured attacks eventually compelled its evacuation, which was nevertheless completed in good order. In the east, the Burgundian southern force, facing somewhat undergunned Polish divisions, broke through and raced along the Greek border, threatening to create a vast pocket centered on Lodz and containing most of the Polish army. After liquidating that pocket, the remainder of the vast Polish nation could be swept up at leisure. By heroic efforts the Yngling and Polish defenders averted this disaster and escaped the pocket after a fierce defence lasting a full month; they were powerless to keep their foes out of the industrial heartland that was Poland proper.

Worse yet, easy victories against strong attacks across Storebælt from occupied Denmark made it easy for OYH to look to the concentration of troops that had ended up around Copenhagen when the Belgians – after a brief naval engagement – landed a diversionary attack in Norrköping. The defending Yngling militia, although brave and well-trained, had no artillery and were rapidly forced to retreat in the face of strong naval support, although partisan risings, just as in the Twenty Years’ War, were immediate and powerful. The Hird divisions pulled out of Copenhagen to deal with this threat to the Swedish metal and industry, on which the Norwegian war effort depended, were indeed able to contain the threat; but their comrades found themselves unable to deal with the renewed thrust of a thousand barrels with battleship support, and were compelled to retreat across Öresund, losing much heavy equipment on the way. Moreover, the tide of victory carried the Burgundian attack into Malmö, where a large part of the Ynglinga Hird was surrounded and eventually compelled to surrender.

At this dark point in the war, when a powerful faction even within the Storting was calling for a negotiated peace – after all, Yngling Norway had been forced to cut its losses before, and might survive to fight another day – world politics intervened. The Kingdom of England, always ready to form a balance against any would-be hegemon, now saw its French possessions directly threatened by Burgundian victory. Yngling unpopularity among the electorate was overcome by a strong propaganda effort in which the suffering of the Polish people took first place. The effects of Britain’s entry were immediate, just as the effects of its exit had been in a previous war; with renewed control of the Baltic, the Overkommando Ynglinga Hird could gather its scattered troops to counterattack. Garrison troops and militia were released by control of the sea from their posts all along the long coastline. The armoured spearheads bogged down in the deep forest and the mountains, where the first breath of winter announced that it would be a hard campaign. Worse yet, what was left of the Ynglinga Hird had recovered its balance and its breath; in hard fighting along the Mjøsa, the Burgundian advance was first slowed, then stopped, and at last reversed.

From Battleship to Barrel : Norway 1920-1953, Bergenhus University Publishing

————————————————

The American situation; I think it may reasonably be called a little confused.

So I made a mistake or two. Mistake number one: Being a newb, I didn’t realise until two sessions into the game that you could abandon a doctrine. Mistake number two: Being impressed with Belgium’s industrial strength, I decided in 1938 that I couldn’t win with the British doctrine path; I therefore switched to the German one. Mistake number three: I thought Belgium would hold off until 1939. So, as you might say, I got caught with my doctrines down, in July of 1938. Then, I did not defend in sufficient depth, and the tanks harried me along, willy-nilly, until full two-thirds the Ynglinga Hird had marched off into captivity.

Even so: Are we not Ynglings? I have lost my good divisions with the strong artillery; the Burgundian rules in Germany and harries the Baltic plain; his panzers stand on the Mjøsa and thrust hard toward Narvik. But now England is in the fight; and winter approaches. It is no joke to fight in Norway in the winter; the mountains and the snows will give us respite. New divisions can be stamped out of the ground; the Poles, with their thousand-year odwaga against the invader, remain strong. This war will not end until it is fought with knives. And we are yet far from that, with these mountains at our back.

And under Dovre, King Olaf stirs uneasily in his sleep.